There is first and foremost a generational divide in the way artists approach the digital sphere. Ceramist Fiona Riley, who still uses a Nokia 3310 and continuously asks me what time my podcast will be running on the wireless, tells me she has absolutely no desire - and, perhaps more importantly - no need, for social media. “I have always sold my art in the real world,” she says firmly. “I’m not technophobic, I have used e-mail since the noughties. I just really don’t need anything else. A lot of the big artists work the same way, you know. [Major YBA artist] only uses [their] phone, here, write it down.”

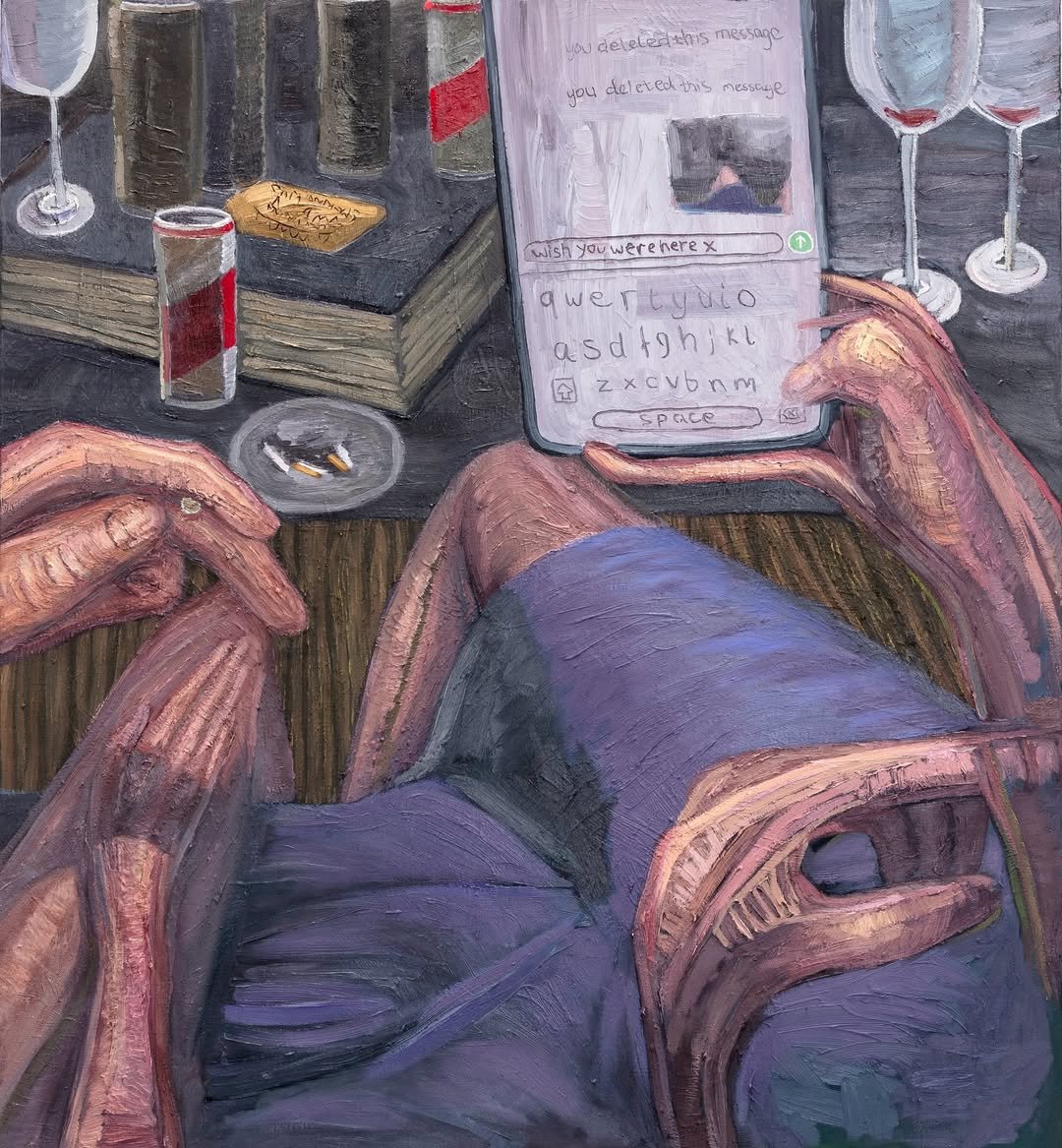

Slightly baffled at having been handed over the landline of possibly one of the most famous British sculptors of the 90s, I call up said number and ask if they feel the same way about social media. They concur, although they present an unexpected anti-angle (and, on brand, refuse to be named): even before the advent of Instagram and Twitter, they had no interest in their works being photographed, arguing that their work “simply doesn’t work” on paper or screens. “I want people to see [my work] in the flesh, never any way else,” they explain. “Sculpture is made to be experienced not visualised. [This is] not something [your generation] understands.” I ask if they think video would fix the problem, and the reply is a firm, slightly offended no. “Even the films that [the blue-chip gallery that shows and sells his work] make the pieces feel predetermined. It’s in my contract that I never want to see photographs of my work, even if it’s in the papers or retrospective [books]. I spend a lot of time picking my galleries, my showrooms. I’m happy to talk about my work but the atmosphere, the lighting, all of these things, that cannot be communicated on a screen, on a photograph, in a book.” A younger, more digitally literate position comes from Columnist at Art Currently, Murph Phi, who treats social media as a kind of accompanying apparatus. “I don’t like to let my actual work interact with social media,” he tells me, but he does “enjoy constructing visual assets adjacent to deliverables for social engagement.” It’s not a refusal of the internet so much as a refusal of the internet’s demand that the work be constantly available as content.