You frequently explore memory, the passage of time, and the tension between decay and resistance, particularly through rural landscapes and abandoned spaces. What draws you to these themes?

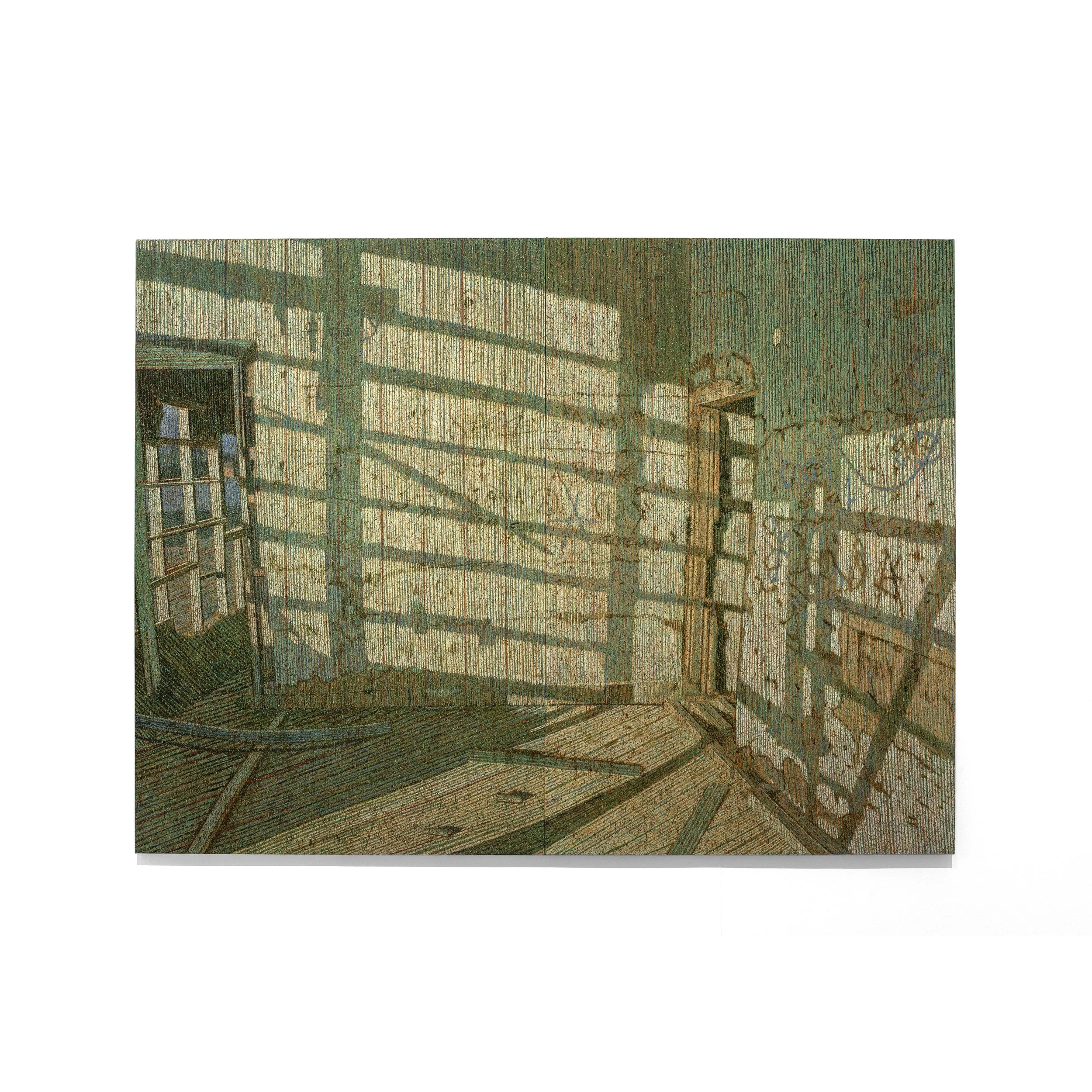

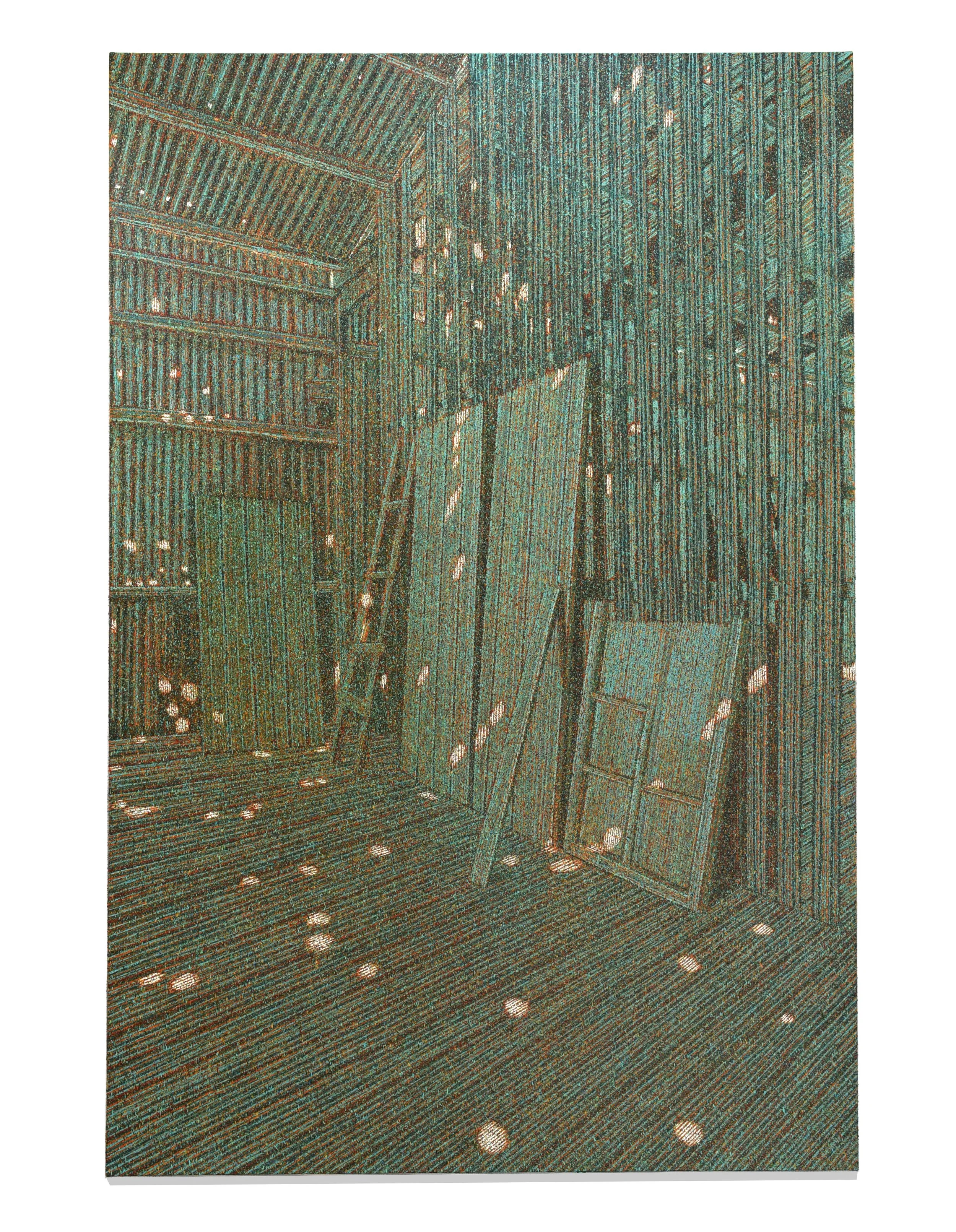

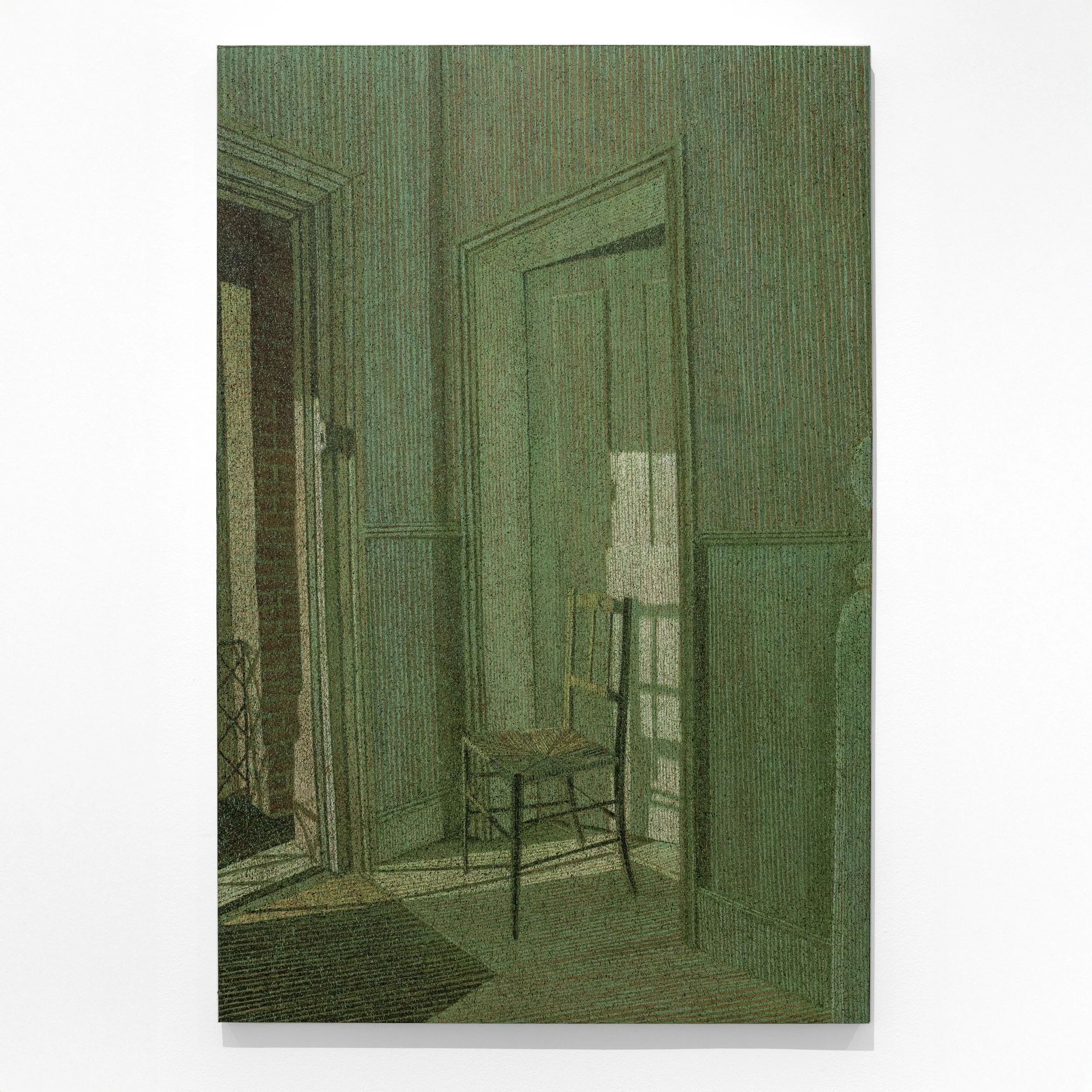

”I believe painting is the most effective medium to talk about absence, what is not physically present within the image. These places allow me to investigate the persistence of absence: how traces of past lives and human experiences remain embedded in the spaces they once occupied. I am interested in the passage of time, in all the accumulated information contained within a wall, a door or a window. At the same time, this poses a challenge for painting: how to translate those images, that experience and that light onto a canvas. I feel that painting also functions as a means of rescuing that archive and memory into something tangible.

I have always been drawn to spaces that contain you, not only physically, but emotionally and spiritually. Their scale, silence and the way light moves within them generate a sense of stillness, introspection and calm. I actively seek out these moments of solitude, and this tendency intensified some years ago as a result of a personal period of mourning. This led me to wander aimlessly through abandoned houses in northern Chile.

I began to pay close attention to the ways in which light entered these spaces unexpectedly, through collapsed roofs and crumbling walls, the wounds of time. I became interested in these unforeseen and suggestive forms, in the spontaneous and random behaviour of light in all its variations. At the same time, there was an adrenaline charge: these places are not without danger. I often find myself so absorbed by the light, attempting to capture the perfect frame with my camera, that I momentarily lose awareness of the risks involved.

To be inside these spaces is to enter a realm suspended in time, where everyday temporality dissolves. Their scale and silence generate a feeling of smallness and vulnerability in relation to what endures, while simultaneously prompting an awareness of the persistence of the past. This experience encourages a slowing down, a contemplative rhythm akin to meditation, where perception intensifies and every detail, the filtered light, eroded surfaces, dust suspended in the air, acquires significance.

Immersion in these environments allows for an intimate relationship with absence. Observation becomes an act of presence, connecting with the memory of the place, its history and the lives that once inhabited it. Time feels suspended, allowing for hours of contemplation without the need for action, simply looking, thinking and breathing, and then, from this experience, attempting to translate the atmosphere and memory of the space into painting.”