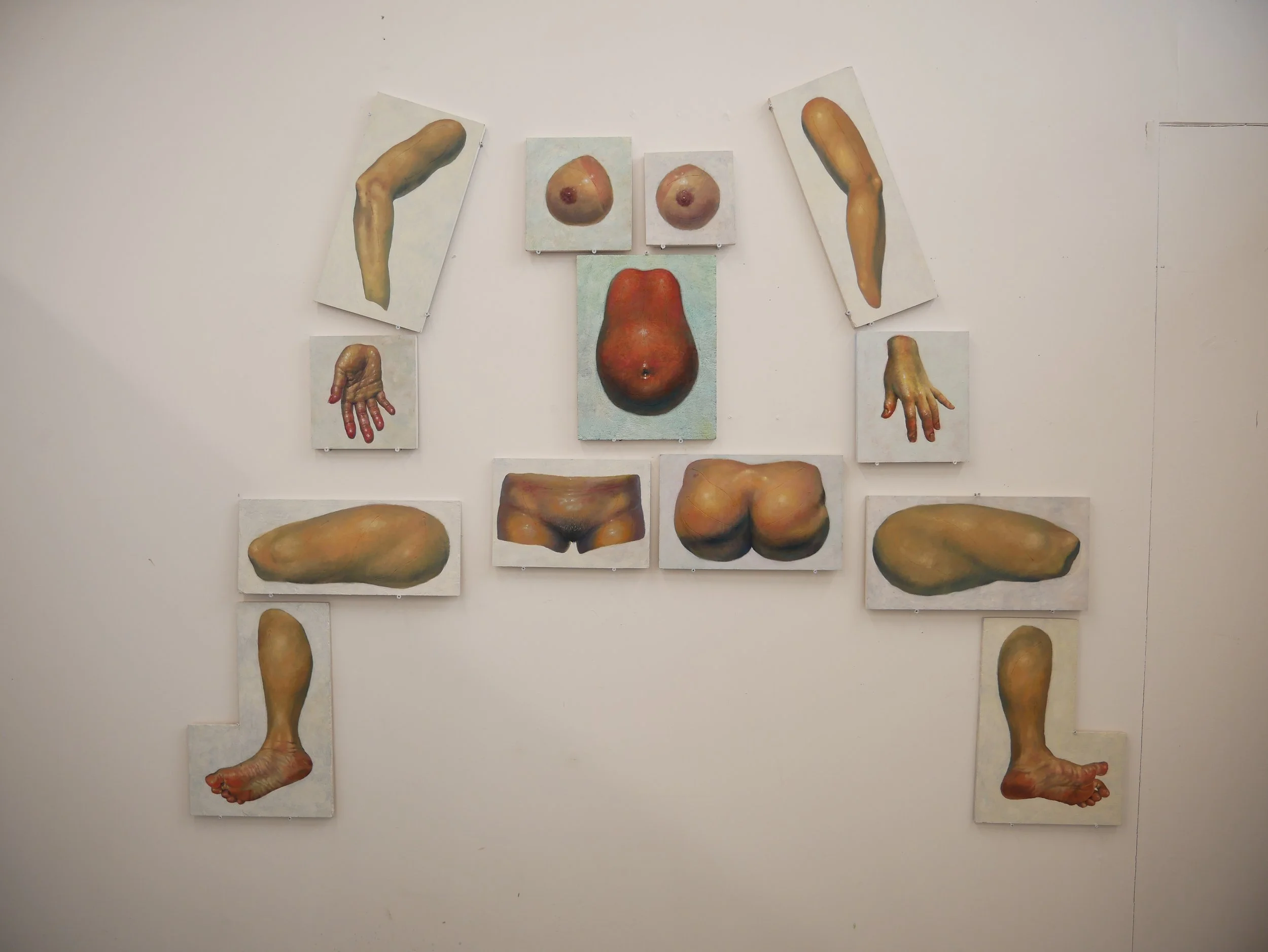

In your Ttaemiri series, you draw from the traditional Korean bathing ritual. What do you hope this ritual communicates to viewers through your paintings?

“The history of public bathhouses in Korea is not particularly long. Of course, Koreans did bathe in the past, but bathing was more of a ceremonial act done on special occasions, such as on Dano (a traditional holiday) or during holidays, or for therapeutic purposes like hot spring baths. However, the widespread cultural adoption of public bathhouses stemmed from a different origin.

In the late 1890s to early 1900s, during the era of Korea’s gate opening to the world, members of the enlightment movement advocated for the establishment of public bathhouses as a step toward becoming a "civilized nation," emphasizing urban hygiene and cleanliness. As Korea entered modernity, the practice of scrubbing the body (ttaemiri) in bathhouses became widespread.

What is particularly interesting is that during the Japanese colonial period, the act of ttaemiri began to be associated with more than just cleanliness and hygiene, it came to carry a sense of inferiority. The Japanese defined Koreans as "unclean," thereby branding Korea as a backward nation in terms of progress. This discourse of power was then replicated across other cultural spheres. The perception that Koreans were colonised because they were less clean than the Japanese was internalised by Koreans themselves, eventually developing into an obsessive scrubbing culture. As colonised subjects, Koreans began to associate the dead skin cells on their bodies as a symbol of impurity that supposed to be eliminated for their independence. It became a residue that needed to be cleansed, not only physically, but psychologically as well.

This historical trauma surrounding bathing practices has now become embedded in what is often seen as an unique aspect of Korean bath culture. I found this ironic and fascinating, and that is what led me to begin the Ttaemiri Series.

Going further, one of the most immediately recognisable elements of the public bathhouse is water. In my work, “water” and “droplets” are crucial motifs. In my paintings, water droplets clinging to the body may seem like they’re about to vanish, but within the image, they remain forever suspended. These eternal, un-evaporating droplets serve as a metaphor for transgenerational trauma, something that stubbornly refuses to disappear. Traces of water, droplets, wet hair, bathhouse tiles, or bathtubs, serve to connect the figures that appear in my paintings. When two different people share a humid space and bathe in the same tub, we can think of them as being linked through the medium of water.

In this way, the bathhouse in my work is both a metaphor for historical and transgenerational trauma, and also a space that allows people to become connected to one another."